GAUDÍ

G Experiència is the only exhibition space in the world dedicated to Antoni Gaudí where you can access to all life and works of the Catalan architect in an interactive format.

INTRODUCTION

The life and work of an innovative architect

Did you know that the Sagrada Família isn’t the only project he left unfinished? Do you know how many works he carried out for the Güell family? Have you ever wondered how many religious buildings he designed?

These are the architectural works by Gaudí you can find at G Experiència. Want to find out all about them using state-of-the-art interactive technology? Come, touch, learn and enjoy.

G Experiència recoge, de forma interactiva, la vida y obra del arquitecto catalán, desde su nacimiento en Reus en 1852 hasta su muerte en Barcelona a los 74 años. Grandes paneles interactivos en 9 idiomas te permitirán descubrir su vida, obra, y proyectos. También podrás contemplar una maqueta del Park Güell y otra del Hotel Attraction de Nueva York, proyecto que Gaudí nunca llegó a materializar.

¿Quieres saber qué vas a encontrar en la exposición? Aquí tienes algunas pinceladas de la información, como la biografía de Antoni Gaudí o sus obras.

“G Experiència no es sólo una experiencia contemplativa, sino una experiencia total, inmersiva, en la que se implican todos los sentidos y todas las dimensiones.”

JOSEP MARIA MAINAT Y TONI CRUZ

Idea y promotores – Crumain Iniciatives

ARCHITECTURAL WORK

A review of the work of Gaudí

Did you know that the Sagrada Família isn’t the only project he left unfinished? Do you know how many works he carried out for the Güell family? Have you ever wondered how many religious buildings he designed?

These are the architectural works by Gaudí you can find at G Experiència. Want to find out all about them using state-of-the-art interactive technology? Come, touch, learn and enjoy.

List of his 27 works

Schools of the Sagrada Familia

(1908-1909)

Consol Bancells

Consol Bancells

Carrer Sardenya and Carrer Mallorca. Barcelona

In 1908, the Association of Devotees of Saint Joseph, a body which decades earlier had sponsored the project of the Sagrada Familia, commissioned Antoni Gaudí to provide a building to accommodate schools for the children of the parish. The new construction occupied land that would later be taken over to build the church’s Passion façade so would eventually be demolished. In spite of the provisional nature and modest dimensions of the project, this building proved to be one of Gaudí’s minor master works. It was admired by famous architects including the rationalist Le Corbusier, who saw it in 1928 and was struck by its beauty and functionality. The schools building was destroyed during the Spanish Civil War and reconstructed once the war ended. At present, moved a few metres to make room for the Sagrada Familia works, it houses a small museum.

The Sagrada Familia schools are a single building the interior of which is divided into three classrooms. They were constructed with brick, a cheap material that was ideal for a project with such a small budget. What stands out is the undulating shape of the walls and roof as well as Gaudi’s original layout which gave the schools an interesting aesthetic quality as well as great structural soundness. In the case of the roof, its sinuous profile also provided a masterly solution to draining off water on rainy days.

Crypt of the Colònia Güell

(1908-1914)

Lluís Casals

Lluís Casals

Carrer Claudi Güell. Santa Coloma de Cervelló (Baix Llobregat)

In 1898 Eusebi Güell asked Antoni Gaudí to build a church for the textile model village he had founded on the outskirts of Barcelona in 1890. The architect proposed an ambitious project, and devoted ten years to preliminary studies during which he developed an innovative “stereostatic” model of the church. The first stone was laid in October 1908 but six years later, in October 1914, Gaudí abandoned the works, after the project became economically unviable for the Güells. The church was to have one upper and one lower nave with 40-metre high towers, but only the first part was ever built, and the project has become popularly known as “the crypt” in its honour.

Although never finished, the Güell village church is considered one of Gaudí’s masterpieces because it anticipates many of the structural solutions that the architect applied to the Sagrada Familia. The entrance porch consists of inclined columns and parabolic and hyperbolic vaults, used here for the first time in the history of architecture. This unique geometric form is repeated in the walls of the church, with a star-shaped profile pierced by large windows whose stained glass combines crosses with plant forms. Both walls and porch incorporate ornamental details in trencadis, using natural and religious motifs. In the interior, Gaudí achieved an open-plan space thanks to the use of inclined stone and brick pillars. Set over these columns, the catenary arches and ribs that support the ceiling constitute one of the most spectacular panaromas in the Gaudí universe.

Torre Damià Mateu, La Miranda

(1906-1907)

Col. Roisin / Institut d'Estudis Fotogràfics de Catalunya

Col. Roisin / Institut d'Estudis Fotogràfics de Catalunya

Carrer Major. Llinars del Vallès (Vallès Oriental)

“La Miranda” is the popular name of a lookout tower built between 1906 and 1907 at one end of the estate in Llinars del Vallès, beside the Giola river bed, where industrialist Damià Mateu i Bisa spent his summers. It was a present from Mateu to his wife, who used it as a sewing room and for meeting her friends. The ground floor was also used as a garage. Only a drawing remains of the La Miranda project, signed by Gaudí’s disciple Francesc Berenguer i Mestres, but some experts believe that Gaudí himself took part in the work and that this like the Güell Wineries in El Garraf would therefore be a cooperation between the two architects,.

The tower, with three floors and a cylindrical profile, was made of brick and board and covered from the observation point upwards with a dome lined with blue and white ceramic trencadis that recalls the coach house in the Güell estate. From one side of the tower to the other ran a wall very similar to that of the Miralles estate surrounding the Mateu property. The entrance gate had a wrought iron grille designed to resemble a fisherman’s net, like the gate at the Güell Wineries. La Miranda was badly damaged in 1939 towards the end of the Spanish Civil War, when a van of TNT of the retreating republican army exploded alongside it. Abandoned for decades, it was demolished in 1962. Only the entrance gate was saved and transferred to Park Güell.

Casa Milà, La Pedrera

(1906-1910)

Fotolia

Fotolia

Passeig de Gràcia, 92. Barcelona

La Pedrera is the last great civil work of Antoni Gaudí, a monumental residential building in the Passeig de Gràcia in Barcelona built for Pere Milà and his wife, Roser Segimón, who set up home in the first floor flat and rented out the four upper floors. To adapt it to the changing needs of a building with many tenants Gaudí made use of revolutionary building techniques. Using a structure of pillars and beams combined with a self-supporting non-load-bearing façade he achieved an interior where walls could be demolished and the layout changed at will. This masterly use of space is a direct precursor of the open-plan developments in nineteen-twenties rationalist architecture. Gaudí also laid out the flats in a functional manner around two large patios to ensure good lighting.

Beyond the structural innovations, however, what is most striking in the Casa Milà is the undulating stone façades with their surprising curved forms that recall the folds of a mountain or a cliff face. On completion, the work’s bold exterior was the subject of great controversy and attracted many negative comments, some of which maintained that the building looked like a quarry (“Pedrera”), a name which has stuck to it ever since. Other butts of popular humour were the original wrought iron railings that Gaudí designed for the balconies. Other unusual spaces in La Pedrera are the attic whose brick catenary arches recall the ribs of a whale, and the fantastic undulating roof terrace that incorporates organic-shaped skylights, ventilators and chimneys that constitute veritable sculptures.

Gaudí abandoned the works at the Casa Milà in 1910 after completing the basic structure due to disagreements with its developers, who rejected his proposal to crown the building with an immense sculpture of the Virgin. Pere Milà and Roser Segimón also objected to the architect’s ideas for the interior decoration although these finally went forward, carried out over the years by collaborators of the architect. This entailed completion of the unusual plaster ceilings, the brilliant murals in the entranceway and the encaustic tiled floors with marine motifs designed by Gaudí himself.

Gardens of Can Artigas

(1905-1906)

Lluís Casals

Lluís Casals

Camí La Pobla – Clot del Moro. La Pobla de Lillet (Berguedà)

In 1905 Antoni Gaudí spent a few days a La Pobla de Lillet to supervise the construction of the Catllaràs chalet. The architect stayed at the house of textile manufacturer Joan Artigas i Alart and in return for his hospitality gave the industrialist the sketch of a design for his gardens at the Font de la Magnèsia, near Artigas’ factory. Some months later Gaudí sent some of the workmen from the Park Güell to La Pobla to help to the local builders to complete the gardens.

Thanks to a system of stone and cement stairs and bridges the Artigas gardens occupy both sides of narrow mountain pass carved out by the River Llobregat. Various elements like a bandstand, a cave and several fountains, fully integrated into the landscape and decorated with allegorical animals representing the four evangelists, make for a restful haven in the midst of nature.

Chalet del Catllaràs

(1905)

Lluís Casals

Lluís Casals

Pista Forestal de la Serra del Catllaràs. La Pobla de Lillet (Berguedà)

In July 1904 in Clot del Moro, in the municipality of Castellar de n’Hug on the bank of the River Llobregat the first Portland cement factory in Catalonia was inaugurated, founded by an industrial group headed by Eusebi Güell. The factory was fuelled by coal mined nearby in the pre-Pyrenean Catllaràs mountains. In 1905 Güell commissioned Antoni Gaudí to design a mountain chalet to accommodate the engineers working at the mine.

The Catllaràs chalet is a simple but clearly Gaudian construction whose shape, a single parabolic vault, is both ideal for the snowy climate on this mountain site and recalls the Güell Wineries in El Garraf. The original cement-clad finish was lost, being replaced with slate tiles and many years ago the double circular stairway that Gaudí designed to connect the different floors disappeared.

Workshop of the Badia brothers

(1904)

Càtedra Gaudí

Càtedra Gaudí

Carrer Nàpols. Barcelona

Between August and December 1904, Antoni Gaudí built the workshop of the brothers Josep and Lluís Badia i Miarnau, wrought iron craftsmen who collaborated in several of the architect’s works under Joan Oñós, setting up on their own after the latter’s death. The workshop which disappeared decades ago was a modest industrial building, small but with an interesting curved roof that anticipated the solution that Gaudí used years later for the Schools of the Sagrada Familia. It was here that the Badia brothers made some of the most brilliant pieces of wrought iron for Gaudí’s works like the railings of the La Pedrera balconies.

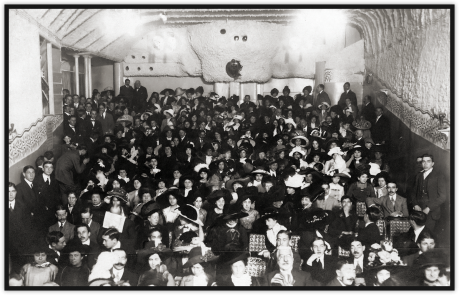

Sala Mercè

(1904)

Arxiu GMN (Antoni González)

Arxiu GMN (Antoni González)

La Rambla, 122. Barcelona

In November 1904 a cinema owned by painter Lluís Graner i Arrufí and built on the ground floor of an existing building by his friend Antoni Gaudí, was inaugurated in the Rambla in Barcelona. This cinema, the Sala Mercè, admitted 200 people and projected its own creations involving the latest cinematography. It also put on musicals and events combining theatre, music and painting directed by the most famous Catalan theatre designers of the day. It was rounded off by a basement display with dioramas set around an artificial cave.

Gaudí’s radical reform of the premises only lasted until 1916 when the building disappeared due to a change of ownership. No images have survived either of the entrance with its wrought iron sign or of the entry to the underground cave, which some say was a homage to the caves of Artà which the architect visited while restoring Mallorca Cathedral. Inside the cinema of which some photographs have survived Gaudí prioritised rational design, making it easier to see the screen and including inclined seating. So as not to distract the public’s attention decoration was kept to a minimum. In spite of this, some interesting details can be seen on the walls including a border with plant decoration and the textured plaster of the walls and ceiling that both improved the acoustics and conveyed the appearance of a cave.

Restoration of Mallorca Cathedral

(1904-1914)

Ramon Manent

Ramon Manent

Plaça de la Seu. Palma de Mallorca (Balearic Islands)

Early in 1902 Pere Campins i Barceló, Bishop of Mallorca, asked Antoni Gaudí to restore the cathedral in Palma de Mallorca. The reform was to include the repair of the façades of the Gothic temple, badly damaged by an earth quake in 1851, and redistribution of the interior. The architect visited the island on several occasions during 1902 and 1903, in October presenting the restoration project. The work was started in 1904 and continued in phases until 1914, when Gaudí abandoned the project before work could be begun on the façade due to disagreement with the contractor.

Gaudí’s alterations to the interior of Mallorca Cathedral clearly demonstrate both his highly developed sense of space and his bold approach. Immune to possible criticism, to make the church brighter and better suited to the liturgy Gaudí dismantled the Gothic choir in the middle of the central nave and displaced it to the sides of the presbytery, where he also dismantled the altarpieces and a tribune. Once he had achieved a unified visual perspective that favoured dialogue between the officiant and the faithful, the architect changed the position of the altar and covered it with a new baldachin. Although in principle this was a provisional model pending the definitive work that was never carried out, it is a prime example of Gaudí’s design.

Casa Batlló

(1904-1906)

Ingrid Pitarch

Ingrid Pitarch

Passeig de Gràcia, 43. Barcelona

The Passeig de Gràcia, the main thoroughfare of the Eixample district, was built in the second half of the nineteenth century. Between late 1904 and early 1906, Gaudí was commissioned by industrialist Josep Batlló i Casanovas to build there what is undoubtedly considered one of his major master works. Although it may seem so at first sight, Casa Batlló was not new but a reform of an existing building. Gaudí transformed its appearance radically, renovating the interior and façades with such original shapes and colours that from the moment the work was completed the building became an icon in the Barcelona urban landscape.

The façade of Casa Batlló, an outburst of Gaudian fantasy, has given rise to many interpretations. Some have compared its curved forms with the waves of the sea, and the ceramic and glass ornamentation that gives it such colour with marine fauna and alga. Others see its cladding as an allusion to confetti at Carnival time, an idea reinforced by the fantasy shapes of the cast iron grilles on the balconies that resemble Venetian masks. The same balconies have also been compared with skulls, and like the surprising bone-shaped columns on the first-floor tribune, are thought to represent the victims of the dragon in the legend of Sant Jordi. The dragon would be symbolised by the roof covered with scale-like ceramics from which rises a tower crowned by a four-armed cross, identified with the sword of Sant Jordi that killed the beast.

Interpretations apart, the main façade of Casa Batlló is a compendium of structural inventions and forms repeated throughout the building: the strange mushroom-shaped chimneys, the back façade with trencadis in natural and geometric shapes, and the beautiful inner courtyard where Gaudí graded the size of the windows and the colour of the ceramic coating progressively to help spread light throughout the interior.

Wall and entry gate of the Miralles Estate

(1901-1902)

Ingrid Pitarch

Ingrid Pitarch

Passeig Manuel Girona, 55-61. Barcelona

Between 1901 and 1902 Antoni Gaudí built the wall and the entrance gate for the estate of his friend, printer and manufacturer of pressed cardboard tiles Ermenegild Miralles i Anglès in Sarrià, an outlying village incorporated into Barcelona in 1921. The architect’s design for the enclosure, of which only a small part is still standing, involved a stone wall and undulating metal grille. The wall joins the gate through a sinuous trefoil arch in which there are two separate doors for carriages and people, also using original curved forms. Two large fibre cement canopies spanning the gate in the shape of a tortoise shell protect both entrances. Finally there are two excellent examples of Gaudí’s wrought iron work: the grille on the pedestrian entrance and the four-armed cross above the gate.

Bellesguard Villa

(1900-1909)

Càtedra Gaudí

Càtedra Gaudí

Carrer Bellesguard, 16-20. Barcelona

On the slopes of Tibidabo in the former village now part of Barcelona, Sant Gervasi de Casseroles, Antoni Gaudí built a family house that looked like an unusual Gothic castle. This is the house, known as Bellesguard due to its fine views, that Maria Segués i Molins commissioned him to build in 1900 on the site where King Martin the Humanist had lived in the sixteenth century. The architect took advantage of some of the surviving ruins to construct an architectural homage to Catalonia’s glorious mediaeval past. Unmistakably a Gaudí construction, Bellesguard is full of references to Gothic art, including its trefoil arches, twin balconied windows and battlements that accentuated its castle-like appearance. The building itself is made from stone and adobe and clad with an innovative stone mosaic, and topped with a great tower finished with the Catalan flag and a four-armed cross. Particularly fine in the interior are the hall lit by a large star-shaped window and the attic, similar to those in the Casa Batlló that Gaudí was building at around the same time.

As well as the house, in the Bellesguard estate there is a slim viaduct constructed by Gaudí in 1908 over the Betlem stream. The following year, the architect stopped work on the villa with some details still unfinished, and it was completed by his disciple Domènec Sugrañes i Gras in 1917.

Park Güell

(1900-1914)

Consol Bancells

Consol Bancells

Carrer d’Olot. Barcelona

In July 1899 industrialist Eusebi Güell acquired a large estate on the Muntanya Pelada in Barcelona where he planned to build an extravagant development deep in the countryside with views over the city, based on the garden city model that was springing up in Great Britain at the time. His idea was to divide the land into 72 plots where each customer would build his own house. Güell commissioned development of the estate and the construction of communal amenities from Gaudí, who started work on the project in 1900. Two years later the first plot was sold, but in spite of all Güell’s efforts no more were bought. In 1914, with the commercial failure of the initiative, Gaudí abandoned the works after completing the site’s basic services. Nine years later, Barcelona City Council bought the Park Güell and opened it as a municipal garden.

Park Güell may have been a failure in business terms, but in architectural and urban development terms it has undoubtedly become one of the most successful and famous of the works of Gaudí, then nearing fifty and maturity as an artist. Inside the estate the architect built a network of paths fully integrated into their environment, compensating for the steep slope of the land by means of highly original viaducts and porticoes. There are several ways in, but the only one built by Gaudí was the main entrance, flanked by two pavilions, one a gatehouse and the other for services, featuring attractive and original soft shapes. Once inside a monumental stairway crowned by a fountain in the shape of a dragon beckons visitors to the central areas of the park: the hypostyle room, a space with 86 Greek-inspired columns designed to accommodate the market, and on top of this the great square which Gaudí surrounded with a unique serpentine bench, decorated with trencadis (ceramic fragments) by his collaborator, Josep Maria Jujol.

Casa Calvet

(1898-1899)

Consol Bancells

Consol Bancells

Carrer Casp, 48. Barcelona

The Casa Calvet was built by the children of textile manufacturer Pere Màrtir Calvet, who set up the business founded by their father in the basement and ground floor, while the first floor was used as the proprietors` home and the upper floors were rented out. This block of dwellings constitutes one of Gaudí’s least bold works, with a symmetrical façade that recalls a modest early Modernisme construction. Only careful attention to the details reveals the architect’s brilliant hand. Of particular interest is the entrance, flanked by columns in the shape of bobbins and an original wrought iron door knocker: a cross that comes down on a bug, symbol of the faith that destroys sin. Over the main door is the colourful first-floor gallery, with sculptural representations of flowers and mushrooms, a shield of Catalonia and references to hospitality (a cypress), peace (an olive branch) and abundance (two horns of plenty). A final point of interest is the façade’s cornice, with three busts of holy martyrs and two balconies of cast iron at the front, anticipating those at the Casa Batlló.

The interior of the building also has Baroque decoration, particularly in the entrance hall, but Gaudí’s main concern was the functional layout of the space. So for example, he placed the inner courtyard near the stairs to give it a better lookout. This was one of the things that the jury of the first annual competition for artistic buildings in Barcelona took into account when awarding their prize to the Casa Calvet in 1900.

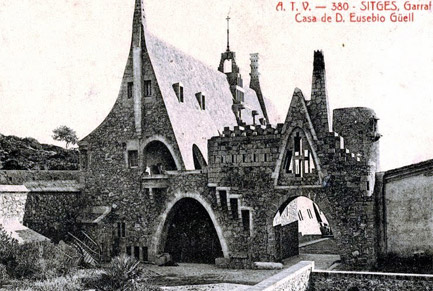

Cellers Güell

(1895-1900)

Wikipedia (Jordi Armengol)

Wikipedia (Jordi Armengol)

Barcelona-Valls road. Sitges (El Garraf)

A group of two buildings on La Cuadra in El Garraf, an estate acquired by Eusebi Güell in 1872, where he produced wine for the ships of the Companyía Transatlàntica. Between 1905 and 1900, Antoni Gaudí and his assistant and disciple Francesc Berenguer i Mestres constructed one building for use as a winery (“cellers”) and another as a porter’s lodge. The stone and brick lodge abuts onto a parabolic arch which forms the entrance to the estate and also holds up the stairs to the guardroom. The iron grille on the gate resembles a fisherman’s net.

The other building, the winery itself, is one of the most fascinating of Gaudí’s creations. Made entirely of stone, it has a surprising triangular profile with the walls following the shape of the gable roof. Inside, above the basement winery are three floors: the first is a garage, the second accommodation for the administrator, and the top floor a chapel that opens on one side onto a terrace with sea views. The winery with its very expressive chimneys is linked by two parabolic bridges to the estate’s original mediaeval country house.

Buildings for the Cooperativa Obrera Mataronense

(1874-1885)

Lluis Casals

Lluis Casals

Carrer de la Cooperativa. Mataró

In his youth, between 1873 and 1885, Antoni Gaudí maintained a close personal and professional relationship with Salvador Pagès i Anglada, a textile industrialist whose views were close to Utopian Socialism and who had founded the Cooperativa Obrera Mataronense (Mataró workers’ cooperative) in 1864, first in Gràcia and from 1874 in Mataró. Gaudí collaborated enthusiastically in planning the cooperative’s premises, working with architect Emili Cabañes and engineer Joan Brunet. He was responsible for the general plan of the buildings and personally designed some, including two workmen’ cottages (built between 1878 and 1879), a social club (projected in 1878 but never built), a public lavatory and the textile bleaching factory.

Only the lavatory and factory have survived. The former is a small cylindrical building with a few ceramic motifs. The bleaching factory, built between 1882 and 1885, is a large simply finished space whose main interest lies its construction with Gaudí’s traditional parabolic arches, used here for the first time and created with wooden structures held together with pins.

Works at Ciutadella Park

(1875-1882)

Fotolia

Fotolia

Ciutadella Park. Barcelona

To pay for his architectural studies, Antoni Gaudí worked as a draughtsman with master builder Josep Fontserè i Mestre, whose family also came from Camp de Tarragona. Between 1873 and 1887 Fontserè directed works at the new Ciutadella Park in Barcelona where the 1888 Universal Exhibition was to be held, and others in the surrounding area including the construction of the Born Market.

Gaudí’s collaboration in Ciutadella Park was not limited to drawing up plans for Fontserè, he also made some contributions of his own. At the park’s monumental waterfall, built between 1875 and 1882, he designed the pavilions leading up to the terrace, the décor of the pool walls and the cave. He was also responsible in 1875 for the stone balustrade in the Placeta d’Aribau, ornamented with lions’ heads, and the following year, for the iron candelabra with the shield of Barcelona on the entrance railings. Gaudí also built the regulating basin of the large tank that stored water for the park, a complex project which he used to pass his degree subject ‘Strength of Materials’ without having to sit the examination.

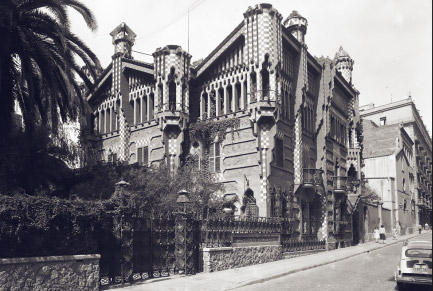

Casa Vicens

(1883-1888)

Càtedra Gaudí

Càtedra Gaudí

Carrer de les Carolines 24. Barcelona

Casa Vicens was the first important commission received by Antoni Gaudí, just after he completed his degree in architecture. He was recommended by Manuel Vicens i Montaner, who wanted to build a summer residence on a plot owned by his family in the village of Gràcia, not yet assimilated into Barcelona. Gaudí presented the project in 1880 but work did not start until 1883 and went on to 1888.

Gaudí designed a four-floored house with a simple structure, still nowhere near the curved lines and architectural innovation of his later work, but interesting for its showy decoration, with fascinating spaces like the dining and smoking rooms. The explosion of colour in its ornamental details, greatly influenced by Arabic and eastern art, make Casa Vicens a clear precursor of the Modernista movement.

Casa Vicens originally abutted onto a convent on one side and a magnificent garden on the other. In 1925, after the convent had been demolished, architect Joan Baptista i Serra extended the house, carefully respecting the original work. The garden disappeared gradually over the years, with the loss of a monumental fountain with parabolic arch designed by Gaudí.

Expiatory Church of the Sagrada Familia

(1883-1926)

Consol Bancells

Consol Bancells

Carrers Mallorca, Marina, Provença and Sardenya. Barcelona

Gaudí’s best known work, now a symbol of Barcelona all over the world, is a sumptuous building to which the architect devoted more than half his life. He took over the works in late 1883 at the age of 31, replacing Francesc de Paula del Villar i Lozano of whose original project only part of the crypt had been built. When Gaudí died in 1926 he was still working on the site, and only the crypt and the apse, part of the cloister and the Nativity façade had been completed. Since then, the process of construction of the church has continued.

Gaudí radically transformed the original architect’s initial Neo Gothic project, conceiving a monumental church of gigantic and unheard-of dimensions. With its layout of space and profuse sculptural decoration it forms a veritable Bible in stone, a mystic poem that both professes and explains the Catholic faith. Once completed, the church will have five naves surrounded by an ambulatory cloister with an apse with seven chapels in the north, and three façades on the other sides: the Nativity, the Passion, and the main façade, the Glory. Each façade will include four bell towers with parabolic profile representing the twelve apostles, and on the apse and crossing, six more towers will symbolise the four evangelists, the Virgin Mary and Jesus. The tower of Jesus on the dome will be the highest, at 170 metres.

Beyond its whirlwind of symbolic and ornamental work, the Sagrada Familia also stands out as the work in which Gaudí combined all the architectural and structural discoveries of his career. With a modular grid floor plan, the church’s structure is supported by inclined pillars forked like the branches of a tree and covered by parabolic naves, an ideal combination for bearing the weight of the imposing construction.

Villa Quijano, El Capricho

(1883-1885)

IStockPhotos

IStockPhotos

District of Sobrellano. Comillas (Cantabria)

Near the Sobrellano Palace Gaudí planned a summer villa which became popularly known as El Capricho for Máximo Díaz de Quijano, a relative of the Marques of Comillas. The villa was built between 1883 and 1885, the works directed by architect Cristóbal Cascante i Colom while Gaudí supervised the whole process from Barcelona.

El Capricho is a relatively small three-floored building in which the layout of the rooms is adapted to fit the sloping site. Its Neo Mudejar appearance recalls Casa Vicens which Gaudí was building at the same time in Gràcia. Of particular interest is the chromatic play of the exterior, combining stone on the base with yellow and reddish brick walls and a glazed tile roof. The front entrance was sheltered by a porch with four columns whose capitals were decorated with flowers and doves, supporting a tower that resembles a Muslim minaret. The tower is clad with tiles representing green leaves and sunflowers, a motif which is repeated in bands running round the walls. The subtle decorative details with frequent allusions to music, one of the Díaz de Quijano’s passions, also stand out in the interior. For example, for the windows of the main first-floor lounge, Gaudí invented an ingenious system that produced the sound of bells when opened and closed.

Pavilions of the Güell estate

(1884-1887)

Lluis Casals

Lluis Casals

Avinguda de Pedralbes, 15. Barcelona

In late 1883 Eusebi Güell added new land to the great estate that was his by inheritance, extending it as far as the former villages of Sarrià and Les Corts and turning it into a summer residence. The industrialist commissioned Gaudí to reform the family home and to build the estate’s boundary wall, including access gates and pavilions. This was the first cooperation of any scale between Güell and Gaudí, and was completed by the architect in 1887. The reform was lost between 1919 and 1924 when the house was converted into the new Royal Palace of Barcelona. Much of the estate’s wall also disappeared as the city expanded, encroaching on the former Güell estate. But in spite of new urban developments, three secondary gates remain, along with the magnificent main entrance, flanked by one pavilion in the form of a porter’s lodge and another for the stables and coach house

The Güell estate’s pavilions are minor masterworks in which Gaudí repeats the Neo Mudejar aesthetics of his youth but also introduces elements that would come to characterise his mature work like parabolic arches and vaults and hyperbolic domes. Among the most interesting ornamental aspects is the combined use on the exterior of brick, prefabricated cement panels and ceramic cladding. However, the most striking element is the wrought iron grille of the carriage entrance which represents one of the mythological passages of Atlàntida by poet Jacint Verdaguer, friend of Güell and Gaudí. This impressive grille reproduces Ladon, the mythological dragon who protected the golden oranges of the Garden of the Hesperides.

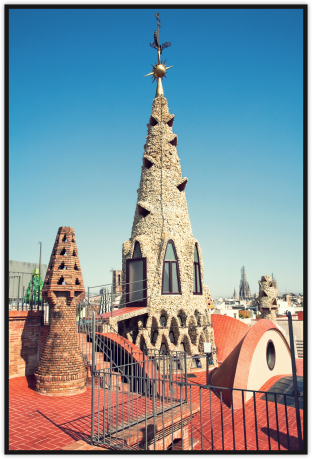

Palacio Güell

(1886-1890)

Fotolia

Fotolia

Carrer Nou de la Rambla, 3-5. Barcelona

The Palau Güell, completed when the architect was only 38, is the culmination of Gaudí’s youthful production, a work in which his total mastery of the use of architectural space became evident. Fascinated by the young architect, in 1885 Eusebi Güell commissioned him to build his residence in the centre of Barcelona, setting no limit on the cost. Gaudí responded with an exuberant, thoughtful work with an almost obsessive attention to detail.

Conceived as both as a home and for social gatherings, the Palau Güell is organised around a central lounge whose height extends up three floors and is covered with a parabolic dome that recalls the night sky. This imposing space served both as a concert room and for family prayers, thanks to an original cupboard that opened to reveal an altar. Around it Gaudí set out the rooms of the palace in a totally functional fashion, creating plays of perspective to give a feeling of spaciousness to a building that in fact occupies a relatively small plot.

As well as its central lounge, other striking features of the Palau Güell are the stables and roof terrace. The former are in the basement, where the exposed brick vaults and fungiform columns constitute an iconic landscape in the work of Gaudí. The aperture in the roof terrace, an exterior projection of the lounge, and the sculptural treatment of the twenty chimneys that surround it are precursors of ideas that the architect was to use later in the Casa Batlló and La Pedrera.

Chaplain's house and workshop of the Sagrada Familia

(1887-1912)

© Fundació Institut Amatller d’Art Hispànic. Arxiu Mas

© Fundació Institut Amatller d’Art Hispànic. Arxiu Mas

Carrer Sardenya and Carrer Provença. Barcelona

As the Sagrada Familia progressed, Gaudí used some of the land to put up some provisional auxiliary buildings, which although modest showed characteristic features of his work. The first to be completed in 1887 was the local chaplain’s house, a two-floored brick-built house with belfry. In 1906 the chaplain moved to a new building built beside the former, with a chapel upstairs and a trencadis anagram of the Sagrada Familia on the façade. Gaudí’s study was then set up in the vacant house where the architect came to live for the final months of his life. Over the years, annexes were gradually added to both buildings. In July 1936, during the anticlerical uprisings that marked the outbreak of the civil war, the study and the chaplain’s house were set on fire. Not only these constructions, but also the whole of Gaudí’s archive were destroyed including many plans and models of his projects.

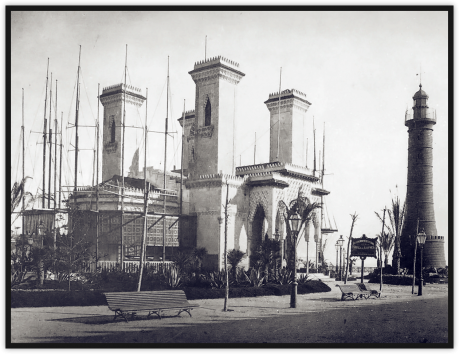

Pavilion of the CompanyíaTransatlàntica

(1888)

Càtedra Gaudí

Càtedra Gaudí

Passeig Marítim. Barcelona

Claudi López i Bru, segundo marqués de Comillas y cuñado de Eusebi Güell, encargó a Antoni Gaudí el pabellón de la Compañía Transatlántica, el principal consorcio de barcos transoceánicos de España, para la Exposición Universal de Barcelona de 1888. A Gaudí no se le encargó un nuevo pabellón, sino adaptar y reformar uno de ya existente diseñado por Adolfo García Cabezas para la Exposición Naval de Cádiz de 1887. Con todo, la intervención del arquitecto fue tan importante que el pabellón resultante prácticamente era una obra nueva, con muchas referencias al arte nazarita. Gaudí añadió al pabellón cuatro torres con almenas, astas con gallardetes, persianas con celosías de madera y una entrada que imitaba el patio de los leones de la Alhambra de Granada.

Ubicado en la sección marítima de la Exposición Universal, el pabellón no se desmontó al clausurarse la misma y permaneció hasta muy entrado el siglo XX, cuando se derribó para construir el actual paseo Marítim de Barcelona.

Teresian School

(1875-1882)

© Israel de la Torre / Sicalipsis estudi

© Israel de la Torre / Sicalipsis estudi

Carrer de Ganduxer, 85-105. Barcelona

Early in 1889 Antoni Gaudí took charge of the works for the school and headquarters of the religious order of the Teresians in the village of Sant Gervasi de Casseroles, now part of Barcelona. Construction of the school had begun the previous year to the project of another architect, which was abandoned when only the foundations had been built. Gaudí respected the initial floor plan but changed the building’s appearance, transforming it into one of his most personal creations.

Unlike many of Gaudí’s works, the Teresian School used few resources in line both with the limited resources of the congregation and the nuns’ vows of poverty. Using cheap material wherever possible, Gaudí designed the school as an original Neo Gothic castle with a façade that combined boarding and brick. The aesthetics of the resulting building incorporate many religious symbols: anagrams of Jesus Christ, Carmelite shields, four-armed crosses on the corner towers, and mortar-boards on the battlements in reference to Saint Teresa. Gaudí’s traditional parabolic arches are present on the façade, in the windows and the access porch, the latter closed with an elegant wrought-iron grille. Arches are repeated inside the building, in the passages that run around the inner courtyard and the form one of the most atmospheric spaces of the architect’s work.

Episcopal Palace in Astorga

(1889-1893)

Fotolia

Fotolia

Plaça d’Eduardo Castro. Astorga (Castile-Leon)

After the old Episcopal Palace of Astorga burned down in December 1886, the bishop, Joan Baptista Grau, suggested to the ecclesiastical and ministerial authorities that his friend Antoni Gaudí should be asked to build the new palace. He presented his project in August 1887, but the works did not start until June 1889, after some objections and many bureaucratic obstacles. Gaudí visited Astorga a dozen times to supervise the work but basically directed it from Barcelona, where he was occupied on other projects. Annoyed by the constant obstacles raised by the authorities, the architect abandoned the work in November 1893, some weeks after the death of his friend Grau. The building was already almost complete apart from the roof, which was finished between 1907 and 1915 by another architect using a very different solution to Gaudí’s original plan.

The Neo Gothic style Episcopal Palace is built using granite from Bierzo to integrate it into its environment and not overshadow the nearby Astorga Cathedral. Its structure is highly conventional, built to a Greek cross floor plan with the ogival arches and cross vaults typical of Gothic architecture. In spite of this, some of its features reveal Gaudí’s originality: the arches in the entrance porch, the elongated chimneys in the shape of minarets, the pit which brings more light into the basement, and the treatment of the interior, recalling the Palau Güell.

Casa Fernández y Andrés, Casa Botines

(1891-1892)

Fotolia

Fotolia

Plaça de San Marcelo. Leon (Castile-Leon)

In 1891 businessmen Simón Fernández and Mariano Andrés commissioned Antoni Gaudí to build the new headquarters of the Fernández y Andrés company in Leon. This banking business was also engaged in the sale of textiles whose buyers included Eusebi Güell, who recommended the architect. Gaudí presented the project in December 1891 and it was started immediately, built in record time and completed in November 1892. The new building soon received the popular name of Casa Botines, in memory of Joan Homs Botinàs, the Catalan businessman established in León, founder of the company which later became Fernández y Andrés.

Like the Episcopal Palace in Astorga, the third and last of Gaudí’s works outside Catalonia was a personal interpretation of the Gothic adapted to suit its environment. The façades were built with rusticated limestone that echoes Gothic Renaissance architecture, a style well represented in Leon, and the roof and four cylindrical towers are of slate, an ideal material for areas with snow and that Gaudí only used in this project. Inside, the ground floor with its wrought-iron pillars provided an open space adaptable to the changing needs of a space used for storage and offices. The same innovative system was applied by Gaudí applied years later in La Pedrera.

PROJECTS NEVER CARRIED OUT

Discover things you sure did not know

Did you know that Antoni Gaudí already started to shine in the subject of projects when he was studying architecture? Or that he designed a monument for a public space in Barcelona? Did you know he started work on a project for a skyscraper for a hotel in New York?

These are some of Gaudí’s projects that never got to see the light of day but which you can find at G Experiència. Want to find out all about them using state-of-the-art interactive technology? Come, touch, learn and enjoy.

List of his 12 projects

Hunting lodge in El Garraf

(1882)

Càtedra Gaudí

Càtedra Gaudí

Sitges (Garraf)

The first important commission Antoni Gaudí received from Eusebi Güell was never realised. This was for a hunting lodge in Güell’s estate on the El Garraf coast, south of Barcelona. Gaudí drew a detailed plan in which we can see the main features of the architect’s first works: an exposed brick building with a large Neo Gothic and Neo Mudejar tower which calls to mind both El Capricho in Comillas and the Casa Vicens.

Street lights for Passeig de Mar

(1880)

Lluis Casals

Lluis Casals

Passeig de Mar (now Passeig de Colom). Barcelona

These were majestic lamp posts for electric street lighting that Gaudí designed for installation in the Passeig de Mar near Barcelona Port after the sea wall had been demolished, starting in April 1878. Gaudí’s collaborator in the project was engineer Josep Serramalera i Aleu, a former student colleague, who would take charge of its execution and who in March 1880 presented the project to Barcelona City Council, who finally rejected it.

Gaudí had two different proposals for the lights. The simpler were to be set on circular stone bases, topped by a city crown and attachment for banners. The more ambitious proposal was for giant lamp posts some 20 metres high, conceived as a homage to Catalan naval success. Set over large jardinières, the lights would support banners with images of the most famous admirals and battles in Catalonia’s history.

Girossi News stand

(1878)

Arxiu Municipal de Barcelona

Arxiu Municipal de Barcelona

Girossi News stand

In May 1878, businessman Enric Girossi approached Barcelona City Council with a proposal for installing twenty news stands in the city that would also act as public lavatories and flower stalls. Gaudí completed the plan for the model, which had a marble base, iron columns and roof with large panes of glass. The young architect’s design contained some ingenious ideas, like including water sprays in the columns to water the plants on sale, and using the glass panes for advertisements. Although the council approved the project its sponsor went bankrupt before it could be carried out.

Degree work

(1875-1878)

Càtedra Gaudí

Càtedra Gaudí

Degree work

The genius of Antoni Gaudí already shone in the works he did as part of the ‘Projects’ subject of his architecture degree. Although not intended to be built, Gaudí’s designs were exhaustive down to the smallest detail. These projects anticipated the monumental feel and symbolism of the architect’s later work in their neo-Mediaevalist style, so in vogue at the time.

The projects presented by Gaudí for his teachers’ evaluation included the door for a cemetery (September 1875), whose plan and decoration represented the New Testament book of the Apocalypse; a yard for Barcelona Provincial Council (October 1876) with an iron and metal skylight which recalls the skylight in the Born Market, then under construction; a sumptuous royal wharf for a lake (November 1876); a monumental fountain for Plaça de Catalunya, Barcelona (June 1877), with elements shared with the Ciutadella Park waterfall in which Gaudí collaborated; and for his final examination (January 1878), the main hall of a university. Gaudí also began projects for a general hospital in Barcelona and a pavilion for the 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia, but these have not survived and it is not clear whether they were ever completed.

Chapel for Alella Church

(1883)

Alella (El Maresme)

Alella (El Maresme)

Chapel for Alella Church

Antoni Gaudí spend some of his summers in Alella, at the villa of his client Manuel Vicens i Montaner, who had commissioned the Casa Vicens in Gràcia. He designed a cupboard and a fireplace for the villa.

His stays in Alella led to Gaudí receiving a commission to build the chapel of the Holy Virgin in the local parish church of Saint Felix, and he presented the design in July 1883. The chapel, of Gothic inspiration, with altar and altarpiece, incorporated many elements inspired by the Apocalypse, including seven large windows with images of the angels of the Last Judgement, which Gaudí would also use in the Sagrada Familia. The chapel was never built in spite of being approved by the bishopric of Barcelona in 1886.

Franciscan Missions

(1892-1893)

Càtedra Gaud

Càtedra Gaud

Tangiers (Morocco)

During the second half of 1891, Antoni Gaudí accompanied the second Marquis of Comillas, Claudio López y López, on a journey through Andalusia and northern Africa, where they visited the cities of Ceuta and Tangiers, where Claudio López intended to fund the construction of some Franciscan missions. After studying the terrain, Gaudí worked on a project throughout 1892 and 1893. Although Gaudí’s proposal was approved by the Capitular Congregation of Tangiers in October 1893, it was never built, probably due to unrest in the area during the first Rif War, although economic problems of his sponsor at the time must also have played their part.

Gaudí’s project, of which only a plan survives, was very ambitious and anticipated some of the solutions that he would apply later like the thirteen towers, very similar to those raised at the Sagrada Familia. The missions would have had a central church surrounded by courtyards and other enclosures for schools and a hospital, surrounded by a circular wall with parabolic doors and hyperbolic windows.

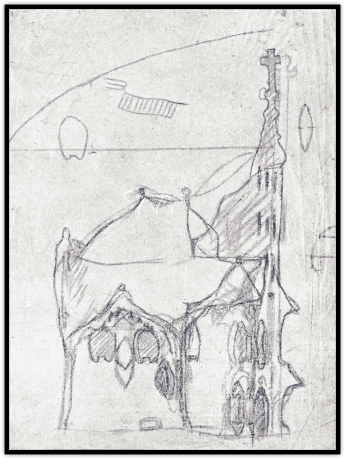

Façade of the Sanctuary of Mercy in Reus

(1903)

Francesc Xavier Fernàndez / IMMR

Francesc Xavier Fernàndez / IMMR

Plaça del Santuari de la Misericòrdia, s/n. Reus (Baix Camp)

In Spring 1903 Antoni Gaudí visited Reus accompanied by some of his collaborators to present a project to the Administrative Board of the Sanctuary of Mercy for the reform of the façades of the city’s Renaissance Gothic church, dedicated to its patron saint. The architect’s proposal of which only a pair of sketches remain envisaged building a monumental porch crowned by a great sculpture of the Virgin. The sanctuary board approved Gaudí’s idea in July 1903 and that same month the council gave him permission to start the works. But they were immediately halted by a disagreement between residents and the board which finally made the project unviable. So Gaudí was unable to complete the only commission he ever had from his native city.

Chalet Graner

(1904)

Carrer de la Immaculada, 44-46. Barcelona

The painter and entertainment impresario Lluís Graner i Arrufí had commissioned Antoni Gaudí to create the Cinema Mercè on the Rambla. He went on to ask him to build him a house in Sant Gervasi de Casseroles, the present Barcelona district of Bonanova. The architect designed a chalet with curved lines topped by a four-armed cross, a cross between the entry pavilions of Park Güell and Casa Batlló which he was then just starting. Although he began the work the project did not go ahead when Lluís Graner could no longer fund it. Only the garden wall and gate, in stone with sinuous shapes, were completed and even they disappeared decades ago.

Monument to Jaume I

(1907)

Càtedra Gaudí

Càtedra Gaudí

Plaça de Ramon Berenguer El Gran. Barcelona

In 1907 Antoni Gaudí was invited to raise a monument to Jaume I in the environs of the Cathedral of Barcelona as part of the commemoration of the seventh centenary of the birth of this king of the Crown of Aragon the following year. The architect responded with a proposal that went beyond a simple statue and involved changes to the urban landscape. Taking advantage of the imminent opening up of a new through road in the district, the future Via Laietana, Gaudí suggested that they should also plan a new square to house the monument. He also proposed to make substantial changes to the finish of buildings nearby including the Cathedral and the Chapel of Santa Àgueda. Gaudí’s ambitious was not accepted, but curiously years later a square was built where the architect had proposed, dedicated to the great-great-grandfather of Jaume I, the Count of Barcelona Ramon Berenguer The Great.

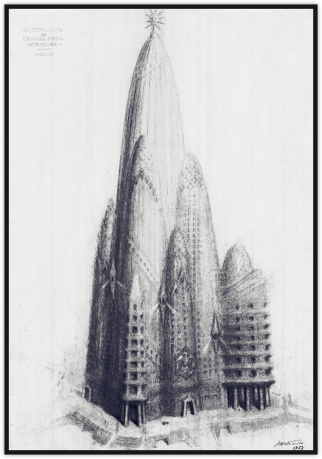

Hotel Attraction

(1908)

Càtedra Gaudí

Càtedra Gaudí

Manhattan. New York (USA)

In May 1908, two American financiers passing through Barcelona approached Antoni Gaudí to construct a hotel on the Manhattan Island. The architect was enthusiastic about the project and made some initial sketches. If it had materialised it would have been one of the most spectacular of Gaudí’s works, but in the end it was rejected due to the financial and technical complexity of its construction which would have taken the best part of a decade.

Gaudí proposed the building as a monumental tourist attraction, with a giant central body 360 metres high with space for guests: five floors with restaurants dedicated to all five continents, several floors for exhibitions and leisure, and at the top on the ninth floor, the Homage to America room, a great space 125 metres high, like an extended version of the central lounge of the Güell Palace, covered with a skylight, that would serve as a privileged vantage point over New York and crowned with an immense star. Around this central building there would have been eight annexes with façades similar to La Pedrera to accommodate the hotel rooms. All nine towers would have had parabolic forms similar to those of the project for the crypt in the Colònia Güell.

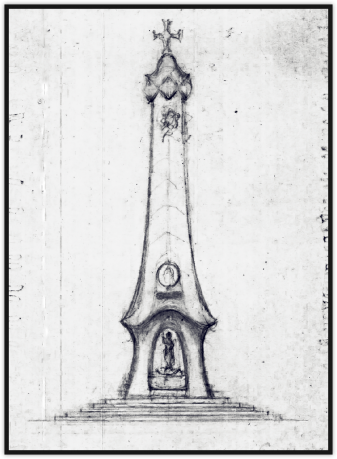

Monumento a Torras i Bages

(1916)

Càtedra Gaudí

Càtedra Gaudí

Carrer Sardenya. Barcelona

On the death in February 1916 of Josep Torras i Bages, Bishop of Vic and intimate friend of Antoni Gaudí, the architect ordered the making of a bust of the priest as a tribute which was dedicated the following April. The sculpture was made by his collaborator Joan Matamala i Flotats and after its dedication Gaudí took it to the Sagrada Familia, where he wished to include it in a great monument dedicated to the Bishop alongside the Passion façade. Gaudí made a sketch of the project but it was never realised, and the bust of Torras i Bages was lost in a fire at the Sagrada Familia workshop in 1936.

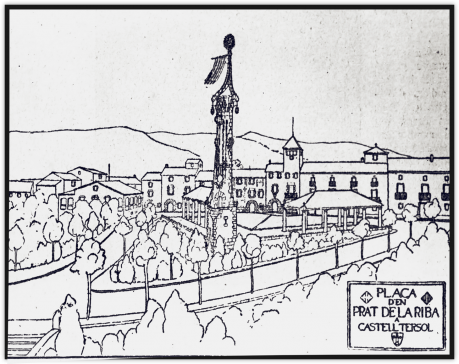

Monumento a Prat de la Riba

(1917-1918)

Càtedra Gaudí

Càtedra Gaudí

Castellterçol (Vallès Oriental)

Antoni Gaudí was a great admirer of Enric Prat de la Riba, the first president of the Commonwealth of Catalonia. After the death of this journalist and politician in August 1917, the architect made a sketch of a monument in his memory but soon abandoned the project. Months later, Gaudí’s disciple and collaborator Lluís Bonet Garí recovered the idea, and in October 1918 presented a project for a monument at Castellterçol, Prat de la Riba’s native town. Bonet Garí’s proposal which was not executed either, included the construction of two porches and between these, a tower decorated with wrought iron and the Catalan flag, of clearly Gaudian inspiration and probably recovered from the original sketches of his master.

DECORATION, FURNITURE AND DESIGN

Discover small secrets of your work

Did you know that Antoni Gaudí also designed the furniture for the Sagrada Família? Do you know how many street lamps Gaudí designed in Barcelona?

These are the pieces of decoration, furniture and design you can find at G Experiència. Want to find out all about them using state-of-the-art interactive technology? Come, touch, learn and enjoy.

23 examples

Desk

(1878)

Càtedra Gaudí

Càtedra Gaudí

Barcelona

Immediately after he completed his degree, Gaudí designed his own desk from a detailed plan noted down in his student’s diary. It had a sliding door and two suspended side compartments which gave it equilibrium. But the most striking feature was its plant and animal decoration, with representations of aquatic plants, birds, snakes and insects. Made of wood and metal, the desk was built in the workshops of Eudald Puntí and Llorenç Matamala and installed in Gaudí’s office in Carrer del Call. Later, the architect took it with him to his workshop at the Sagrada Família, where it was destroyed by fire in 1936.

Furniture and bandstand for the first Marquis of Comillas

(1878-1881)

Ramon Manent

Ramon Manent

Chapel-mausoleum at Sobrellano and gardens of the Marquis of Comillas’ house. Comillas (Cantabria)

Impressed by Gaudí’s work on the showcase for the Comella glove factory, Eusebi Güell commissioned the young architect to design some furniture for his brother-in-law, Antonio López y López, one of the most important businessmen in Spain. Antonio López had just received the title of Marquis of Comillas, and to celebrate this had arranged for the Palace of Sobrellano and an adjoining chapel-mausoleum to be built in his home town. For the chapel Gaudí designed benches, chairs and kneelers, all decorated in carved bass-relief incorporating plant and animal forms (dragons, dogs and eagles).

The chapel-mausoleum and Gaudí’s furniture were inaugurated in summer 1881 during a visit of the royal family to Comillas. Antonio López gave Gaudí another commission for this event: the construction of a bandstand to ornament the gardens of his house in Villa Càntabra, which the architect resolved with a structure of wood, iron and glass, of oriental influence. After the death of the first Marquis in 1883 the bandstand was moved to the Güell estate in Les Corts (formerly a village and now part of Barcelona), where it remained until it disappeared.

Lamp posts for Barcelona City Council

(1878)

Lluis Casals

Lluis Casals

Plaça Reial, Passeig Nacional and Pla de Palau. Barcelona

Through the offices of architect Joan Martorell i Montells, in February 1878 Antoni Gaudí was commissioned by Barcelona City Council to design a model lamp post to provide gas street lighting. The following June Gaudí, recently graduated, presented his project with two proposals for lamp posts, one with six branches and the other with three. Although the lamp posts were planned for several sites across the city, in the end the council only erected the six-branched version in the Plaça Reial, inaugurated in September 1879. Eleven years later, four more were installed, all with three branches, two in Pla de Palau and a further two in Passeig Nacional. The latter pair were taken down in the early twentieth century.

Gaudí’s lamp posts have a marble base and cast iron structure with interesting use of polychrome in golden, red and blue tones. The young architect enhanced the monumental aspect of the lamp posts by giving them symbolic elements like the shield of Barcelona in the centre of the wood, with inverted crowns on top in the three-branched versions, and on the six-branched post, a snake with a winged caduceus, symbol of Mercury the god of commerce.

Banner and decoration for the Cooperativa Obrera Mataronense

(1874-1885)

Lluis Casals

Lluis Casals

Banner and decoration for the Cooperativa Obrera Mataronense

As well as several architectural works, Gaudí was responsible for some decorative elements at the Cooperativa Obrera Mataronense. In 1874 he designed the emblem of the textile cooperative, in which a pair of bees (symbol of hard work) flew over a loom surrounded by thistles. This design was probably the same as the one he used in the organisation’s banner, embroidered by sisters Pepeta and Agustina Moreu, teachers at the cooperative and which has now disappeared. The sign was crowned by a metal bee, one of Gaudí’s works which has survived.

Gaudí was also commissioned to decorate the cooperative’s bleaching factory, which he himself had built, for a party there on 27 July 1885. No images of the event have survived, but from contemporary accounts we know that the architect decorated the space with a waterfall surrounded by vegetation.

Glass display case for the Comella glove factory

(1878)

Francesc Xavier Fernàndez / IMMR

Francesc Xavier Fernàndez / IMMR

Barcelona-París

Esteve Comella, owner of a luxurious glove shop in Carrer Avinyó in Barcelona, commissioned Gaudí to produce a glass display case to exhibit his products at the Paris World’s Fair, inaugurated in May 1878. The architect designed an original construction of wood, iron and glass crowned with metal plant forms inside which the gloves were exhibited on a shelved structure.

Gaudí’s showcase was received with great enthusiasm by visitors and the Comella stand was awarded the fair’s silver medal. Among the admirers of this small gem at the Paris fair was Catalan industrialist Eusebi Güell i Bacigalupi. On returning to Barcelona he made arrangements to meet the showcase’s young creator. Introduced by Esteve Comella at Eudald Puntí’s cabinetmaker’s workshop, Gaudí and Güell soon became friends and so began a fruitful professional relationship.

Altar and decoration of the Church of Jesus Maria of Sant Andreu del Palomar

(1879-1881)

Josep Maria Melcior

Josep Maria Melcior

Parish of Sant Pacià and School of Jesus Maria of Sant Gervasi. Barcelona

When his sister died in 1879 Gaudí was left in charge of her daughter, Rosa Egea, and he sent his niece to the School of Jesus Maria in Tarragona. His contact with this religious order led to him receiving some commissions. The first was for items for the church of the order’s school in Sant Andreu del Palomar, now a district of Barcelona. The church itself was constructed between 1876 and 1881, and from 1879 onwards Gaudí produced a Neo Gothic altar, a Byzantine-style monstrance, a Roman-inspired floor mosaic and a set of wall candelabra. The altar and monstrance were destroyed when the church was set on fire during Tragic Week in 1909. Inside the church, which currently belongs to the parish of Sant Pacià, only part of the mosaic remains, made from colourful pieces of marble, glass and terracotta that trace out geometric and floral shapes. The candelabras have been conserved separately, in the school of Jesus Maria at Sant Gervasi de Casseroles, taken there by the nuns in 1890 when the school at Sant Andreu was sold to the Marist brothers. In these original gilded wood wall lights the candle is held in the open mouth of a winged dragon.

Decoration of the Gibert pharmacy

(1879)

Càtedra Gaudí

Càtedra Gaudí

Passeig de Gràcia, 2. Barcelona

In 1979 Antoni Gaudí received a commission to decorate the pharmacy of Joan Gibert Casals thanks to the mediation of Eusebi Güell, whose family like Gibert‘s came from near Tarragona, in Torredembarra. Gaudí designed almost everything for this pharmacy in the Passeig de Gràcia of Barcelona, sadly demolished many decades ago: the shop sign with the owner’s name, two panels on either side of the entrance with reliefs of snakes (the symbol of medicine), the glazed door and the lateral shop windows with their engraved plant decoration, an elegant carved wooden bench, and a marquetry counter with geometric ornamentation. All in all, an early display of Gaudí’s mastery as designer of wooden furniture.

Altar of the Chapel of Jesus Maria in Tarragona

(1880-1884)

Càtedra Gaudí

Càtedra Gaudí

Chapel of Jesus Maria in Tarragona. Tarragona (Tarragonès)

The only work Gaudí created in his native province is the altar for the chapel of the school of Jesus Maria in the city of Tarragona. This was one of two commissions that he received from this religious order, to which the architect entrusted the education of his niece when he became her guardian. The architect’s intervention in the chapel began after it was blessed in December 1879 by its vicar, Joan Baptista Grau i Villaspinós, who years later as Bishop of Astorga would commission Gaudí to build the city’s Episcopal Palace.

In beautiful polychrome, the altar is made of alabaster and marble, its front graced with three angels in relief on a blue ground with gold stars. Behind, two marble steps bear the imposing gilded wood cylindrical monstrance with two angels, one on each side. Gaudí also designed a group of seats of honour, which disappeared in 1936 at the start of the civil war as did the monstrance, although this was later recovered.

Decorative elements for the gardens of the Güell Estate

(1884-1885)

© Fundació Institut Amatller d’Art Hispànic. Arxiu Mas

© Fundació Institut Amatller d’Art Hispànic. Arxiu Mas

Avinguda Diagonal. Barcelona

As well as reforming the family house and designing the boundary wall and entry pavilions for the gardens of Eusebi Güell’s estate at Les Corts and Sarrià, Antoni Gaudí designed some decorative and leisure elements and oversaw the planting of Mediterranean trees and shrubs. The architect also built two lookout sites at the estate boundary wall and on the roof of the house, a pergola with iron parabolas, and two fountains, one dedicated to Santa Eulàlia and the other to Hercules. To these must be added the oriental temple built in 1881 for the gardens of the Comillas villa of Antoni López, who moved to the Güell estate in 1883. Except for the Hercules fountain which is still extant, all these pieces were destroyed in the first third of the 20th century during works on the Palau Reial estate, when a coach house constructed by Gaudí inside the gardens was also destroyed.

Altar for the Bocabella chapel

(1885-1890)

Càtedra Gaudí

Càtedra Gaudí

Carrer Mirambell, 4. Barcelona

In 1885 bookseller Josep Maria Bocabella i Verdaguer, patron of the Sagrada Familia, commissioned Antoni Gaudí to design an altar for his house. Bocabella obtained a papal licence to celebrate mass in his private chapel in late 1890 when the altar must already have been complete. Today the piece is owned by a private collector.

The altar is mahogany, with both the feet and the predella decorated with plant motifs. The altar stone has a cavity for holding relics and in the centre of the altarpiece is a tabernacle, with three angels and door lined with damask bearing the letters Alpha and Omega. The piece is completed by portraits of Saint Francis of Paola, Saint Teresa of Jesus and the Holy Family, crowned by a border of leaves in fabric and wood.

Furniture for the Crypt of the Colònia Güell

(1913-1914)

Lluís Casals

Lluís Casals

Carrer Claudi Güell. Colònia Güell. Santa Coloma de Cervelló (Baix Llobregat)

Before abandoning the works on the church at the Colònia Güell, in October 1914 Gaudí designed some items of furniture. His intention was to leave the lower aisle furnished and the crypt ready for the expected opening for worship, which finally occurred in November 1915. Gaudí designed the door of the sacristy and the benches for worshippers, pieces executed by the carpenters of the Colònia, Tomàs and Enric Bernat. The architect was also responsible for the church’s unusual font, made from large scallops shells brought from the Philippines secured with wrought iron. Other furniture and liturgical items of the crypt were installed after Gaudí left the works.

Furniture for the Sagrada Familia

(1885-1926)

Càtedra Gaudí

Càtedra Gaudí

Carrers Mallorca, Marina, Provença and Sardenya. Barcelona

Antoni Gaudí designed some furniture and liturgical objects for the church of the Sagrada Familia. Most of this was for the crypt, where the first mass was held on 19 March 1885 although masses were not celebrated regularly until 1890 and the church was not in parish hands until 1907. The architect also directed and supervised decorative work for the crypt’s chapels with their altars, and the entrance doors to the sacristy.

Of the church’s furniture, Gaudí was responsible for designing benches and chairs, cupboards for the sacristy, a confessional and a portable pulpit, all made by carpenter Joan Munné. Other liturgical items in wrought iron and bronze included lecterns, lamps for the chapel of Sant Josep, and a great triangular candelabrum. For the font Gaudí used a great sea scallop as in the crypt of the Colònia Güell. Some of these objects disappeared in the fire in the Sagrada Familia crypt in 1936 at the start of the Spanish Civil War.

Pulpit for the church of Santa Maria in Blanes

(1912)

Càtedra Gaudí

Càtedra Gaudí

Plaça de l’Església. Blanes (La Selva)

Antoni Gaudí made two pulpits for the church of Santa Maria in Blanes, commissioned by journalist Joaquim Casas, brother of the famous Modernista painter Ramon Casas. Gaudí designed two hexagonal pulpits decorated in accordance with their location in the church. The pulpit on the Gospel side bore the names of the four Evangelists and the dove of the sacred spirit. The other on the Epistle side incorporated the name of the four Apostles who wrote the epistles and representations of the theological virtues, and the fire of Pentecost. Both pulpits disappeared in a fire at the church when the Spanish Civil War broke out in July 1936.

Decoration and furniture of the Palau Güell

(1888-1890)

© Fundació Institut Amatller d’Art Hispànic. Arxiu Mas

© Fundació Institut Amatller d’Art Hispànic. Arxiu Mas

Carrer Nou de la Rambla, 3-5. Barcelona

The Paul Güell was officially inaugurated in 1888 to coincide symbolically with the Barcelona International Exposition. However the building was not yet ready and two more years were required to complete the works, the decoration and the furnishing. Güell and Gaudí employed some of the most important artists and craftsmen of the day, including architect Camil Oliveras on the dining room and some of the chimneys; painter Aleix Clapés who produced the paintings in the lounge; and decorator Francesc Vidal from whom Güell commissioned most of the furniture.

Although a collective work, Gaudí supervised all ornamentation of the Palau and himself designed many elements in which his signature can be detected. Of particular interest are the wrought iron grilles of the parabolic arches and guard house windows in the entrance, executed by Joan Oñós; the coffering throughout the interior, both decorative and structural, made by Eudald Puntí; and the parabolic chimneys in the bedrooms. Of the furniture, Gaudí designed a chaise longue for Güell’s wife, and an original dressing table with a full-blown Modernista aesthetic for his older daughter. Neither of these items of furniture are currently in the Palau Güell.

Lamp posts for the Plaça Major in Vic

(1910)

Càtedra Gaudí

Càtedra Gaudí

Plaça Major Vic (Osona)

In spring 1910 Antoni Gaudí went to Vic for a period of repose, accompanied by the Jesuit father Ignasi Casanovas. His stay in the capital of Osona coincided with preparations for the celebration of the centenary of the birth of Vic philosopher Jaume Balmes, and the organisers asked the architect for ideas for the event. Gaudí proposed the restoration of Balmes’ birthplace and placing a fountain and two monumental street lights in the Mercadal, Vic’s main square. Only the street lights were made to the architect’s design and directed by his disciple Josep Canaleta. They were inaugurated on 7 September 1910 and remained in the square until August 1924, when they were taken down.

The street lights in the square were monumental structures, built from basalt blocks joined together by iron bands and crowned with four-armed iron crosses. The lamps were supported by iron arms shaped like branches and one of the two also sustained metal sheets bearing the dates of the birth and death of Jaume Balmes.

Furniture in the Casa Calvet

(1899-1900)

Ramon Manent

Ramon Manent

Carrer Casp, 48. Barcelona

After completing the Casa Calvet Gaudí designed a set of furniture for its owners, made at the Casas i Bardés workshops. For the Calvet family flat, the architect made sofas, armchairs and chairs for the main living room as well as two mirrors for the hall and chairs for the dining room. The gilded wood with wrought iron and cord upholstery lounge furniture still shows the style of Gaudí’s early designs, But the hall mirrors and dining-room chairs, carved from oak to form sinuous profiles, already reveal the bolder side of the architect as designer. The same organic forms are repeated in the furniture for Calvet’s offices on the ground floor. The curves of this excellent set of desks and ergonomic seats anticipate Surrealist aesthetics.

First Mystery of the Glory of the Monumental Rosary at Montserrat

(1907)

Lluís Casals

Lluís Casals

Camí de la Santa Cova. Montserrat (Bages)

In 1893 Jaume Collell i Bancells, Canon of Vic, proposed the erection of a “rosary” of monuments between the Monastery and the Holy Cave of Montserrat paid for by private individuals and Catholic brotherhoods. The project, launched in 1896 and completed twenty years later, entailed the construction of fifteen sculptural groups representing the fifteen mysteries of the Virgin.

In late 1900 Antoni Gaudí received a commission to direct the First Mystery of Glory, an allusion to the Resurrection of Jesus, paid for by the Spiritual League of Our Lady of Montserrat founded by Josep Torras i Bages, Bishop of Vic and personal friend of the architect. Gaudí created a sculpture that was in harmony with its environment, in a cave excavated into the rock where an angel and the three Maries watch over the sarcophagus of Jesus while the resurrected Christ appears on the wall above.

Due to problems with funding the works of the mystery did not start until spring 1907 and Gaudí left the project a few months later when it was again halted by economic difficulties. By then only the cave had been excavated and the sculpture of Christ by Josep Llimona i Bruguera mounted on the wall. The project was completed between 1913 and 1916 by another architect, Jeroni Martorell i Terrats, and the missing figures were created by sculptor Dionís Renart i Garcia.

Standard of Reus residents in Barcelona

(1900)

Càtedra Gaudí

Càtedra Gaudí

Reus (Baix Camp)

On 22 April 1900 a pilgrimage was made to the sanctuary of the Virgin of Mercy of Reus, to celebrate the turn of the century. Gaudí participated as a member of the group of Reus residents in Barcelona, presided over by a standard designed by the architect himself. It consisted of a bamboo cane with metal overlays, topped by a cross and a Virgin of Mercy in aluminium. Below on the insignia in embossed leather was an image of shepherdess Isabel Besora, who tradition had it was visited by the Virgin in 1592 (on the front), and the rose of Reus on a shield of Catalonia (on the back), the whole surrounded by a rosary with aluminium and bronze beads.

Fifty standards were displayed during the procession, three of which were chosen as an offering to the Virgin, including Gaudí’s. The work was destroyed in a fire at the Sanctuary of Mercy in July 1936.

Banner of the Association of Locksmiths and Blacksmiths of Barcelona

(1906)

Càtedra Gaudí

Càtedra Gaudí

Barcelona

In all his works Antoni Gaudí collaborated with some of the most outstanding wrought iron workers in Barcelona, including Joan Oñós and the brothers Lluís and Josep Badia. This meant he had a good relationship with the Association of Locksmiths and Blacksmith of the Catalan capital. In 1906 the association’s governors commissioned him to make their banner in which Gaudí featured the embroidered image of Saint Eloi, patron saint of the association, standing out on a green background and rounded off with a shield of Barcelona from which hung ribbons in the colours of the Catalan coat of arms. The banner was lost in 1936.

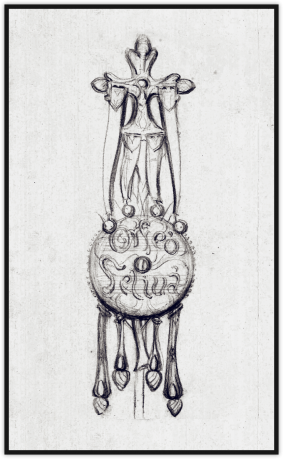

Standard of the Orfeó Feliuà

(1900)

Càtedra Gaudí

Càtedra Gaudí

Sant Feliu de Codines (Vallès Oriental)

In 1900 textile businessman Emili Carles-Tolrà i Amat commissioned Antoni Gaudí to make a standard for his aunt, the Marques of Sant Esteve de Castellar, to present to the Orfeó Feliuà, a choral group recently founded in Sant Feliu de Codines. Made in cork with brass overlays and leather straps, Gaudí’s standard incorporates curious symbolic details like the round form bearing the name of the Orfeó, an allusion to the martyrdom of Saint Feliu on a millwheel, and the pineapples which hang from the straps, in memory of the former name of town: Sant Feliu del Pinyó.

Decoration and liturgical furnishings for Mallorca Cathedral

(1904-1914)

Ramon Manent

Ramon Manent

Plaça de la Seu. Palma de Mallorca (Illes Balears)

As part of the restoration of Mallorca Cathedral, Antoni Gaudí did not confine himself to a masterly redistribution of the interior, he also personally directed the decoration of some of this space as well as designing several liturgical elements. The architect encircled the presbytery with a beautiful wrought iron grille. Within this area he placed four columns around the altar featuring wrought iron decorations, and soaring over the whole raised a spectacular baldachin, suspended from the ceiling, which in turn supported a series of oil lamps. In the Royal Chapel he decorated one wall with ceramic plaques representing the coats of arms of the Bishops of Mallorca and glazed the rose window and two other large windows with polychrome glass. On the first two columns in the central aisle he located two new pulpits while on the others he placed wrought iron candelabras. Particularly striking among the furnishings was a folding staircase for the exposition of the Holy Sacrament made of wrought iron and wood and with elegant curved banisters. Gaudí also designed benches for celebrants at the altar, stools, a faldstool and a lectern.

Decoration and furniture of the Casa Batlló

(1904-1906)

© Fundació Institut Amatller d’Art Hispànic. Arxiu Mas

© Fundació Institut Amatller d’Art Hispànic. Arxiu Mas

Passeig de Gràcia, 43. Barcelona

Inside Casa Batlló Antoni Gaudí not only redistributed the existing layout of the pre-existing building in a totally functional manner, he also decorated it from top to bottom. The architect used plaster on the walls and ceiling to give them sinuous organic shapes and combined wood and glass in the windows and doors to striking effect.

The highly original decorative details of Casa Batlló reached their maximum splendour in the first floor where the proprietors lived. The stairway in the private vestibule with references to the vertebra of an animal, a hearth featuring mushroom shapes and the main lounge with its large windows and doors decorated with coloured stained glass and a series of original wall cupboards, one of which originally contained the family chapel with liturgical objects made by Gaudí’s collaborators. In the dining room the architect personally designed all the furniture including a fascinating group of ergonomic oakwood chairs and benches.

Arab Room of the Cafè Torino

(1902)

© Fundació Institut Amatller d’Art Hispànic. Arxiu Mas

© Fundació Institut Amatller d’Art Hispànic. Arxiu Mas

Passeig de Gràcia / Gran Via. Barcelona

On 20 September 1902, Italian businessman Flaminio Mezzalana opened the CafèTorino on one of the most prestigious street corners of the Eixample district of Barcelona. This was a luxurious establishment where you could drink Martini & Rossi vermouth, of which Mezzalana was the distributor in Spain. The new bar soon became a favourite meeting place for the city bourgeoisie. No luxury was spared in its building and Ricard de Capmany, its decorator had some outstanding collaborators including architects Josep Puig i Cadafalch and Pere Falqués i Urpí and sculptor Eusebi Arnau i Mascort. In spite of its initial success, the Torino closed shortly before its tenth anniversary.

Antoni Gaudí’s contribution was the decoration of an Arab Room, designing the motifs of the wooden wainscoting and wall and ceiling tiles. The tiles were made of pressed and varnished cardboard, a new technique developed by Hermenegild Miralles i Anglès, the printer for whose estate Gaudí was building a wall and entranceway at the time.

BIOGRAPHY

Do you know Antoni Gaudí’s personal history? You will find all the information about the life of the Catalan Architect in Gaudí Experiència’s interactive walls.

Antoni Gaudí i Cornet was born on 25 June 1852 in Camp de Tarragona. Some sources say in Reus, where he was baptised, and others at the house in Riudoms, the neighbouring village, where his family came from. His father and both his grandparents were boilermakers, and as Gaudí himself recounted, he learned his special skill in dealing with three-dimensional space by observing boilermakers at work. Another key fact in the architect’s childhood was his delicate health which forced him to spend long periods convalescing at home in Riudoms. There he spent many hours contemplating nature, drawing lessons that he was to apply later in his architecture.